Why Gypsum?

It’s a popular soil and water amendment. Why? What is it, and what makes it so widely recommended and used?

Gypsum [CaSO. 4· 2H2O] is calcium sulfate dihydrate, a mined mineral that is technically a sulfate mineral, but its calcium “tagalong” is what makes it sought after as a soil/water amendment. It provides a high amount of calcium per pound, per dollar, has a relatively high solubility rate compared to limestone (its greatest competition), and a minimal effect on pH, all of which put it a few steps ahead of the alternatives in most situations.

Gypsum can be used for several agronomic purposes, but it is especially good at combating the effects of poor water chemistry on soil structure. For this reason, it is used generously in areas where water sources are either low in calcium (which strips calcium from the soil) or relatively high in soil-deflocculating ions, like sodium. Low-calcium or imbalanced water sources cause the soil (especially heavier-textured clay soils) to become deflocculated, collapsing the pore spaces and preventing water from infiltrating.

Applying sufficient soluble calcium can help prevent deflocculation and restore soil structure.* Where water chemistry is very imbalanced, or soil calcium depletion is severe, a large amount of calcium may be required. Gypsum is a very effective material for delivering large amount of calcium in most situations, with the exception of low-pH soils (where limestone is preferable). Other calcium materials could also be effective, but gypsum is the most economically viable option with the fewest drawbacks.

*Practices that build soil aggregation (cover crop, compost, minimal pesticides) are also important for fully restoring soil structure. Good soil structure is both flocculated and aggregated.

Is it Better to apply gypsum to the soil or through the irrigation?

Gypsum can be applied to the soil or injected through the irrigation system, and each method has its benefits and limitations.

Field–spread application:

- Requires water to solubilize gypsum and carry it into the soil, so they are more efficient in flood- or sprinkler-irrigated fields, or when applied prior to significant rain events. With drip irrigation alone, a bulk of the applied gypsum does not get incorporated/activated efficiently.

- “Field spread” gypsum has a larger particle size, is less expensive and is available at varying purities and grades

- Solution-grade gypsum can be applied directly to field but is more expensive

- Can be applied with traditional amendment spreaders

- Are typically done only once or a few times a year, due to ease of access for equipment and logistical concerns

- Can show fast improvements in infiltration, often within 1-2 irrigations

- Effects usually do not last full season, typically running out mid-summer

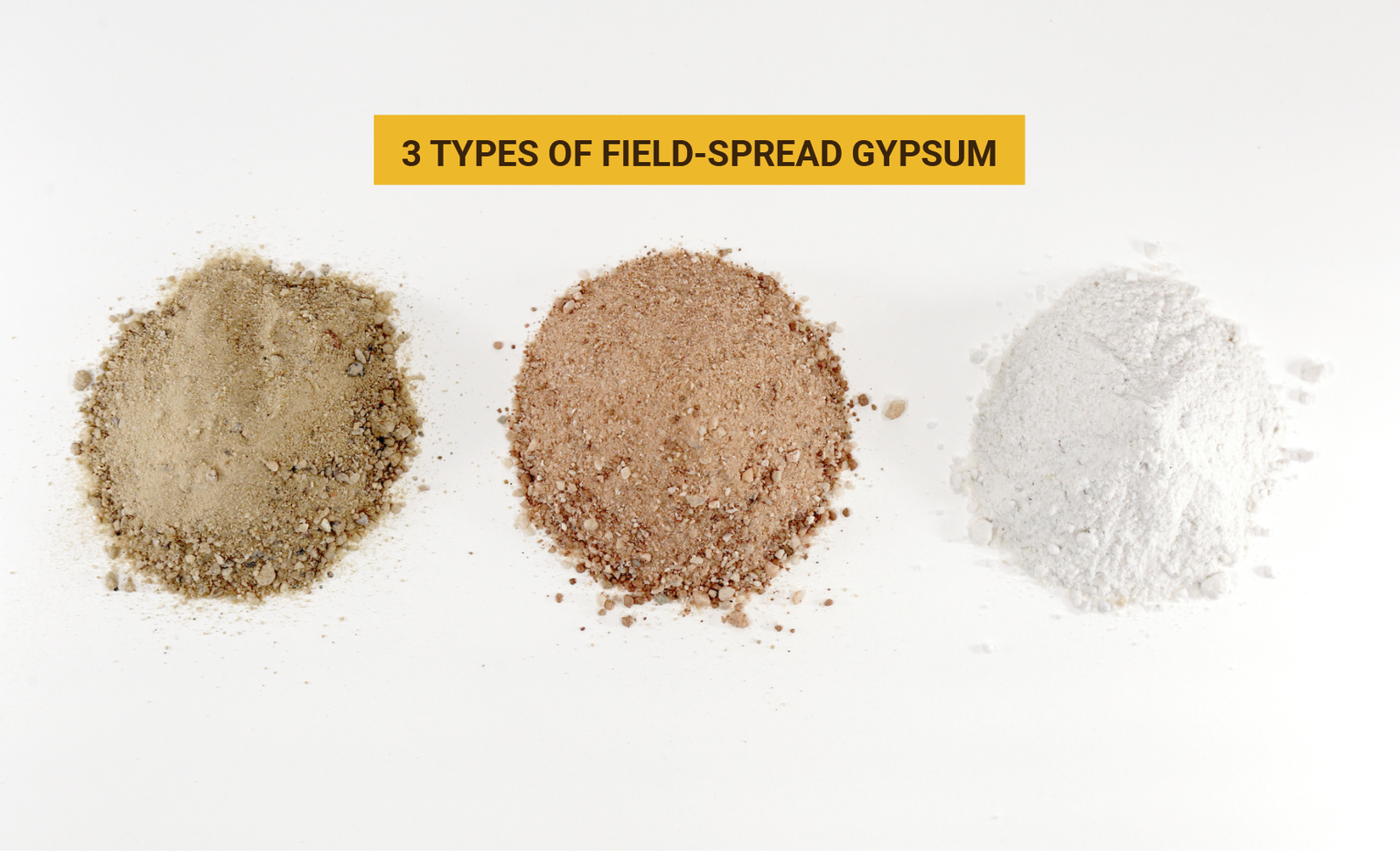

Below are some examples of field-spread gypsum. It can be tan, pink or white, and has a sandy texture.

Water-run application:

- Require specialized application equipment due to gypsum’s low solubility

- Require a high-purity, fine grind (and somewhat more expensive) form of gypsum called “solution grade.” The high purity and small particle size are required for the gypsum to be fully solubilized in the irrigation system, and with minimal impurities

- Should be applied every irrigation event, at a rate to balance out the water chemistry as well as prevent further deflocculation

- Primarily used to fix water chemistry issues

Below is an image that shows a comparison between field-spread gypsum and solution-grade gypsum. Notice the powdery texture of the solution-grade, compared to the granular, sandy field-spread.

Both application methods are useful in addressing poor water chemistry and poor infiltration due to deflocculation. Water-run applications are best for preventing soil structure problems due to poor water chemistry. Either water-run or field-spread applications can be used to address existing deflocculation, or sometimes together, depending on the situation.

But “Solution Grade” is Barely Soluble!

True. Due to the nature of calcium sources, getting them into solution is a challenge, even for solution-grade gypsum which is by far the most soluble of the options. For example, take a look at the rate of solubility of gypsum, as compared to a commonly-used dry fertilizer, potassium nitrate:

While 4 spoonfuls of potassium nitrate dissolved within 2 minutes, a single spoonful of solution-grade gypsum was still cloudy after 20. How, then, do we get gypsum into solution as efficiently as possible?

Enter: Gypsum applicators

Gypsum applicators are machines designed to effectively apply large amounts of solution-grade gypsum through the irrigation water, which would otherwise be a very labor-intensive, spoon-feeding process. There are two commonly used styles of gypsum applicators: the cone-bottom applicator and the box style applicator. Below are some in-field examples.

The cone bottom and box-style applicators function differently (scroll down for a rundown on how each works), but they both use the same, simple 3-step process to get gypsum into solution.

From DRY to dissolved: the 3-step process

The process goes like this: WET. DILUTE. DISSOLVE.

- A large amount of gypsum is WET with water and turned into a thick, concentrated slurry (flowable “solid”)

- The concentrated gypsum slurry is DILUTED with additional water, forming a diluted slurry

- The diluted slurry is injected into the irrigation line during an irrigation event, at a low enough rate (and where there’s enough turbulence) that the remaining undissolved gypsum is DISSOLVED (aka. in solution) and can safety go through the irrigation system.

Through this process, a gypsum applicator is able to “spoon-feed” an irrigation system as much gypsum as it can handle at one time. It’s like trying to eat a whole bowl of cereal in one bite/gulp, versus taking one bite at a time. The latter takes more time, but effectively achieves the goal and avoids the inevitable mess of too much at once.

It’s a simple concept, once you see it in action. Watch this video clip for a tabletop example.

Each step happens a little differently in each style of applicator. For example, box-style applicators get a full tank of gypsum wet at once, while the cone-bottom applicators use a wobbler sprinkler at the base of the cone to wet a small amount of gypsum at a time. For step two, the box-style applicators have a dilution chamber, while the cone-bottom applicators use a float box. Check out the diagrams below to see how each style does it.

Note: Some cone-bottom applicator setups skip step 2 (the float box), using a venturi injector instead to apply the concentrated slurry directly into the irrigation system at a very low rate. This setup works well but has some limitations, so the use of float boxes is becoming more and more common.

Summary

When it comes to addressing imbalanced water chemistry and/or deflocculated soil, soluble calcium is often recommended, and gypsum is the most cost-effective calcium source. Choosing between field-spread and water-run application methods depends on the rate needed and other logistical factors. For water-run applications, a gypsum applicator gets solution-grade gypsum into solution efficiently, avoiding plugging issues and wasted material, and to allowing for the greatest efficiency.